Best Defense of the A-10 This Year

As part of our antitransformationalist canon, one thing we have discussed here on a regular basis since the F-35 came in to being was this; regardless of what people may say – it cannot and will not be able to conduct close air support as it is required.

It is too tender, too ill-armed, too fast, and its crews will never have the detailed practical training needed.

The worst thing for the A-10 was that the USAF owns it – and if she can’t have it, no one else can either.

The army will try to fill the gap with attack helos, but that is imperfect as well.

I suppose That Was You, VI

I suppose That Was You V was posted April, 13.

Every ferry pilot has thought of and has his own opinion of ditching in the ocean. We’ve all seen the two diagrams in the back of the pilot’s operating manual that depict your two options when it comes to landing in the water. According to the experts you’re either supposed to land parallel to the swells or on the back or downhill side of a swell. The manual always has a picture of what not to do, land directly into a swell.

Of course drawing a picture on a piece of paper is a lot easier than breaking out of the clouds at four hundred feet and trying to time your impact point while flying a disabled aircraft that’s on fire.

When the Mooney broke out of the clouds the pilot saw he was already set up parallel to what appeared to be eight to ten foot swells. Dropping the flaps to reduce the stall speed the pilot held the flaming aircraft in the air as long as he could before the plane hit the water, skipped once then nosed in violently.

Both men quickly released their seat belts and scrambled out onto the wing as the smoking plane bobbed in the waves, slowly sinking. The pilot pulled the lanyard that inflated their raft and both men were able to step right in without even getting wet.

Once in the raft the former pilots turned sailors got the bad news, good news, bad news routine. The first bit of bad news they discovered was that the light weight survival suits they both were wearing didn’t keep them very warm at all. The suits they had were a thinner kind that were made of rubber and nylon versus the thick neoprene “Gumby” suits that most ferry pilots wear. Another weak point of the light weight suits was that they just had rubber cuffs around the wrists, ankles and neck as opposed to the thicker suits that only exposed your face.

The good news was that the raft they were sitting in was a good one that had the most important feature you could have in the North Atlantic, a cover. Once zipped up, a cover kept them out the wind and waves and kept the occupants from being knocked out of the raft in the event it got flipped over by large waves.

The next bit of bad news came after they got the cover up and the pilot got out his ditch bag. In the bag he had a few things that would be useful in the event of a water landing; a small flare gun, space blanket, water bottle and most important of all a portable Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT).

An ELT is a small radio transmitter that broadcasts a strong emergency signal that search planes can home in on. In the business of finding a small raft in the huge expanse of the North Atlantic search and rescue teams will tell you an ELT is the single most important piece of equipment you can have.

When the pilot pulled the ELT out of its case he noticed the battery cover was cracked and leaking battery acid. He opened the cover and was dismayed to find the batteries old and leaking and that the insides were corroded and ruined. The ELT was useless.

With nothing else to do the two men huddled together for warmth and waited while their raft rode up and down the swells.

They didn’t have long to wait. After less than three hours in the water the castaways heard engine noises approaching. They un-zipped the raft cover and were overjoyed to see a big grey Canadian Air Force C-130 rescue plane heading almost right at them. The pilot quickly grabbed his flare gun, fired into the air and was rewarded by seeing the rescue plane bank its wings and head for the raft. The two men yelled for joy and waved their arms as the big four engine turboprop overflew them and banked steeply to circle back. On the second pass the C-130 made a lower pass and dropped a line of flares into the water to mark the raft’s position. The pilot of the rescue plane did such an accurate drop that the men had use one of the raft’s oars to fend off one of the floating flares that got too close.

The C-130 circled a few more times then made a pass where they dropped what appeared to be a torpedo close to them. Not knowing what it was they didn’t bother to try and retrieve it, a decision they came to regret because they later found out that it was a well-stocked fifteen man life raft that had everything in it but a mini bar and a hot tub.

The two pilots continued to watch the circling rescue plane for quite a while until the cold ocean spray reminded them that a C-130 is not a seaplane and although they had been found, actual rescue was still some time away. When the men tried to put the cover back up they discovered that they’d made a huge mistake by leaving it down for so long. The zipper for the cover was coated with frozen sea spray and their bare hands were too cold and numb to clear it. The cover was rendered useless and the pilots were now exposed to the relentless cold wind and spray.

Reduced to wrapping themselves up in one flimsy silver space blanket and taking whatever shelter they could under the un-zipped cover the two men waited for rescue. With no radio to talk to the C-130 they had no idea how long a wait they were in for.

After flying at 180 knots for three hours the pilots in the Mooney had covered over five hundred miles before the loss of oil pressure had forced them into the ocean, far beyond the range of any rescue helicopter. Their only chance of being picked up was by ship. Unfortunately ships are much slower than planes and even the fastest Coast Guard vessel launched from Newfoundland would take well over forty hours before reaching them. With the cover on the raft stuck open it was unlikely the pilots could last that long under those conditions.

The crew of the C-130 knew that without a cover they had to get help to the men as soon as possible so they put out a call on the maritime emergency frequency channel asking for assistance from any ships in the area. Miraculously a fishing vessel responded that they were in the area and could be there in eight hours. In terms of ocean speed and distance they were practically next door.

True to their word the crew of the fishing boat hauled their latest catch of two very cold and miserable pilots aboard eight hours later, cold but alive.

The ferry pilot telling me that story said the crew of the fishing boat did a great job of hauling them aboard despite the large swells and the poor condition of the pilots. They cut their fishing trip short and headed right back to St. Johns, a trip that took them four days.

We talked for a few minutes more, both agreeing that he was extremely lucky to be alive. Before we parted ways I tried to get as much information from him as I could about the ditching and time spent in the raft. Any information I could get about surviving in the North Atlantic could only help if I ever found myself in that situation.

After leaving St. Johns for the Azores I spent a lot of time that day staring down at the waves far below, imagining myself sitting in a small raft and waiting for rescue. I’d been told by the airport manager in Wick, Scotland, that on average three ferry pilots a year die crossing the Atlantic. That figure alone sent shivers up my spine but what I couldn’t shake was the image of being in a raft at night slowly freezing to death as the waves tossed me about like a toy. It wasn’t one of my more enjoyable flights.

Fatigue

Summer is here so it’s time to go down to Texas and pick up the 900 horsepower Super Grand Caravan for another season of skydiving in Wisconsin. I was hoping to have the same pilot we had last year fly for us but he went and got a real job flying for a cargo company. Loser. Just kidding, I’m just disappointed because he was a great pilot. I flew down to Houston commercial hoping to just jump into the plane and fly home but when I arrived at skydive Spaceland I was greeted to this sight.

Does that plane look like it’s ready to go? No, no it does not.

There’s no reason to go over everything still needed fixing but the list was long and there was nothing to do but dig in and help the mechanic put Humpty Dumpty back together again. When the sun set the Caravan was still in a thousand pieces so I got to spend the night in a bunkhouse that so nice and beautiful that I could have stayed there forever. Not. The next day we got back to work early and by 6:00 had the plane mostly back together. The owner assumed that I’d spend another night and leave in the morning but seeing it was only a 6 hour trip I figured there was no reason to spend another night in che bunkhouse. I had been concerned about a line of thunderstorms along the route to Wisconsin but as I flew north they seemed to just move out of the way, leaving a beautiful sunset in their wake.

The rest of the flight was a treat. I love night flying and it was a great night to fly. After one fuel stop and five and a half hours in the cockpit I was getting close to my home airport. The sky was clear for most of the last half of the flight but weather report at my home airport was reported to be 1200 feet overcast. Flying as 1200 feet doesn’t bother me especially in my own backyard so when I got close to the airport I dropped down low in order to get under the overcast layer and land. When I got down to 2200 feet on my altimeter the lights on the ground were starting to look pretty darn close. I thought to myself that when I needed to drop down to 1200 feet to get under the clouds it was going to be kind of scary. But that didn’t make sense, it shouldn’t be any big deal to fly at 1200 feet. What was I missing? It only took 30 seconds or so to figure out my mistake but it was an embarrassing 30 seconds. “Kerry you moron! Your altimeter is reading sea level the 1200 foot overcast ceiling is above ground level.” And seeing that the ground level in that part of Wisconsin is about 1000 feet I was already flying at 1200 feet above the ground. It wasn’t the worst mistake in the world but it did show that working all day then flying all night can take its toll. Even an easy flight can be a killer.

A Man After My Own Heart

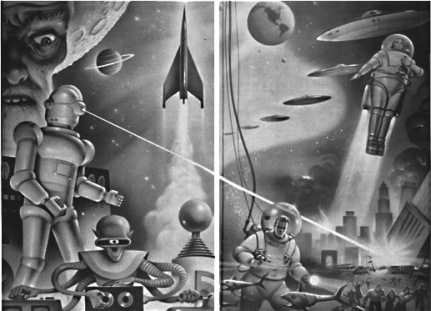

Channeling Heinlein

Finally, a space ship that lands just like the ones in the science fiction books I grew up reading. Pretty damn cool. I wonder how they are planning to enter the earth’s atmosphere? I would think that if they are planning on riding the engine down it would take a ton of fuel. I guess we’ll see.

Why Skids Are More Dangerous Than Slips

An interesting write-up on one of the biggest killers in aviation, the base to final stall/spin crash. The article does a good job of showing the different effects between a skid and a slip.

You may have heard that a skid during a stall is more dangerous than a slip, and it’s true. But, why?

Stall-spin accidents have been a problem since the first days of flight. Most of us are simply taught to keep an aircraft coordinated when stalling. But, the problem is, most stall-spin accidents don’t happen during an intentional stall. They usually happen unintentionally and down low – like when you’re turning base to final.

Here’s a common scenario: You’re turning left base to final, but you’re going to overshoot the runway. What do you do? Here’s what you absolutely shouldn’t do: You add left rudder to tighten the turn, but you don’t keep the bank and rudder coordinated – putting the airplane into a skid.

What can happen next is pure disaster. The skid causes an over banking tendency, which you counter by adding opposite aileron (often subconsciously). That also pulls the nose down, which you oppose with elevator. Suddenly the aircraft stalls and snaps to the left in an incipient spin. At 700′ AGL, you make it through about a turn before you crater into the ground.

“Just get in the plane and go!’

How ‘pilot pressure’ leads to fatal aircraft crashes in Alaska and Outside

In the wake of the records release this week on a fatal 2013 crash involving an Alaska State Troopers helicopter, the circumstances surrounding an earlier flight, to Kodiak in 2009, have come into sharp focus. An interview between National Transportation and Safety Board investigators and Sherry Hassell, the troopers’ Aircraft Section supervisor who retired in 2013, raised the issue of pilot pressure on that flight. According to her statement, Hassell recalled:

Shortly after she started work for the section, this pilot was asked to fly a Cessna 208 to Kodiak Island and pick up some people. After checking the weather, he informed her that the weather was not good and he did not want to go. When she informed the colonel (Commander of AWT), the response was that the pilot needed to “get in the plane and go.”

Alaska Public Safety Commissioner Gary Folger, the former commander named in Hassell’s statement, has denied the implication that he influenced pilot Rod Wilkinson’s decision to take that flight, insisting in an email to the Anchorage Daily News that “I have never made someone fly, it’s entirely up to the pilot.”

The issue of pilot pressure has been part of the aviation landscape in Alaska since its earliest days. Kotzebue airline owner Archie Ferguson was infamous for pushing his pilots to fly, as recounted in this 1943 observation by author Jean Potter in her book “The Flying North”:

He is driven to distraction when one of his men is weather bound away from Kotzebue. “Christ,” he will yell over the radio, with other airway stations listening. “I suppose yer boozin’ or God knows what yer doin’. The weather’s fine here. Come on back!” He is enraged when one of the pilots muffs a takeoff from Kotzebue’s frozen winter runway. He will stand by the field jumping, hitching up his pants, shouting and swearing. “Christ, hurry up! I’m losin’ five hundreds bucks a day! Oh Jeezus, I guess I’ll have ta do all the flyin’ myself!”

Unless you do nothing but fly in the immediate vicinity of your home airport on beautiful sunny days every pilot at some time or another will experience pressure to fly. Sometimes it’s a demanding boss who losing money every minute you sit on the ground waiting for better weather. Sometimes it’s your passengers who can’t understand why they have to miss that important meeting because of poor conditions along the route. And sometimes the pressure come from you. Many pilots, me included, get into a can do, must do, get the mission done at all costs attitude. They rationalize that they’ve flown in such conditions, or worse, before and if they made it then they can make it again. Sometimes they’re right and sometimes they’re wrong. It can be a tough call but sometimes the bravest thing a pilot can do is to call it a day and go have a beer.

Skeliton Of The Sahara

I know I posted the story about the P-40 found in the desert a few months ago but I someone sent me this link to a more complete story with more and better pictures.

My Uncle Denis, pilot of the plane time forgot: First pictures of the man who crash-landed his plane in the Sahara and then walked off across the sands to his death

Oops

The SMY Hohenzollern II

The SMY Hohenzollern II